Research

Neural circuit diversification

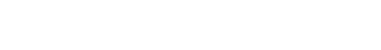

Complex, learned motor skills involve the coordination of activity across multiple neural types and brain regions. How do such interconnected neural circuits co-develop? And what can these developmental mechanisms tell us about the evolution of neural circuits and the behaviors they support?

Birdsong is controlled by a dedicated set of interconnected brain regions that is highly distinct from nearby sensorimotor regions, providing an excellent system to understand the molecular mechanisms that support neural circuit diversification. The lab uses cell-resolved molecular assays, spatial transcriptomics, and gene manipulations in songbirds to study these mechanisms.

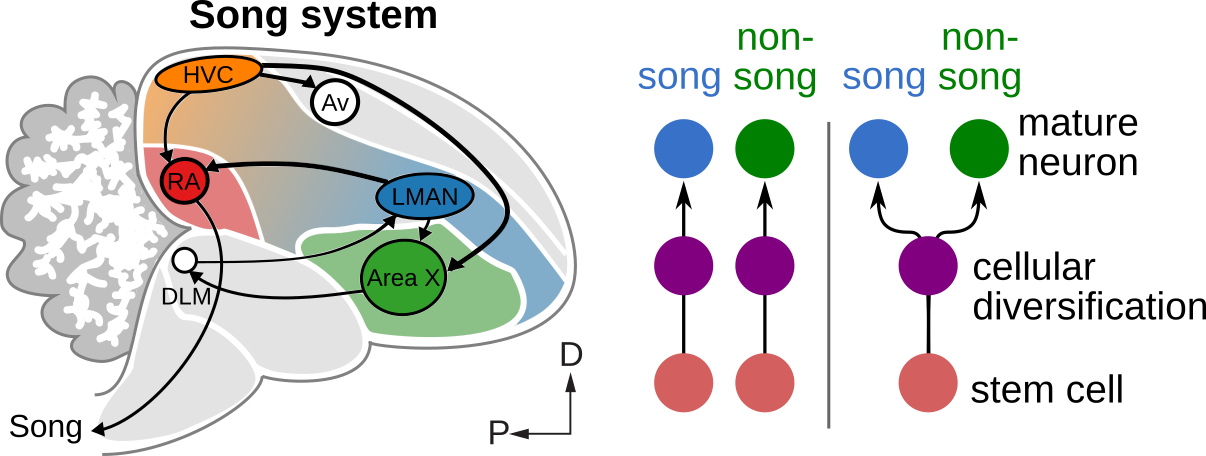

Influence of experience on sensorimotor circuit development

Vocal learning in humans and many songbirds features a sensitive (critical) period for learning during early postnatal development, suggesting that vocal learning circuits begin in a plastic state that is sensitive to auditory signals and then transition to a stable state that is optimized for performance. The lab studies the molecular mechanisms in vocal learning circuits that mediate this transition from plasticity to stability and whether these mechanisms can be leveraged to increase neural plasticity.

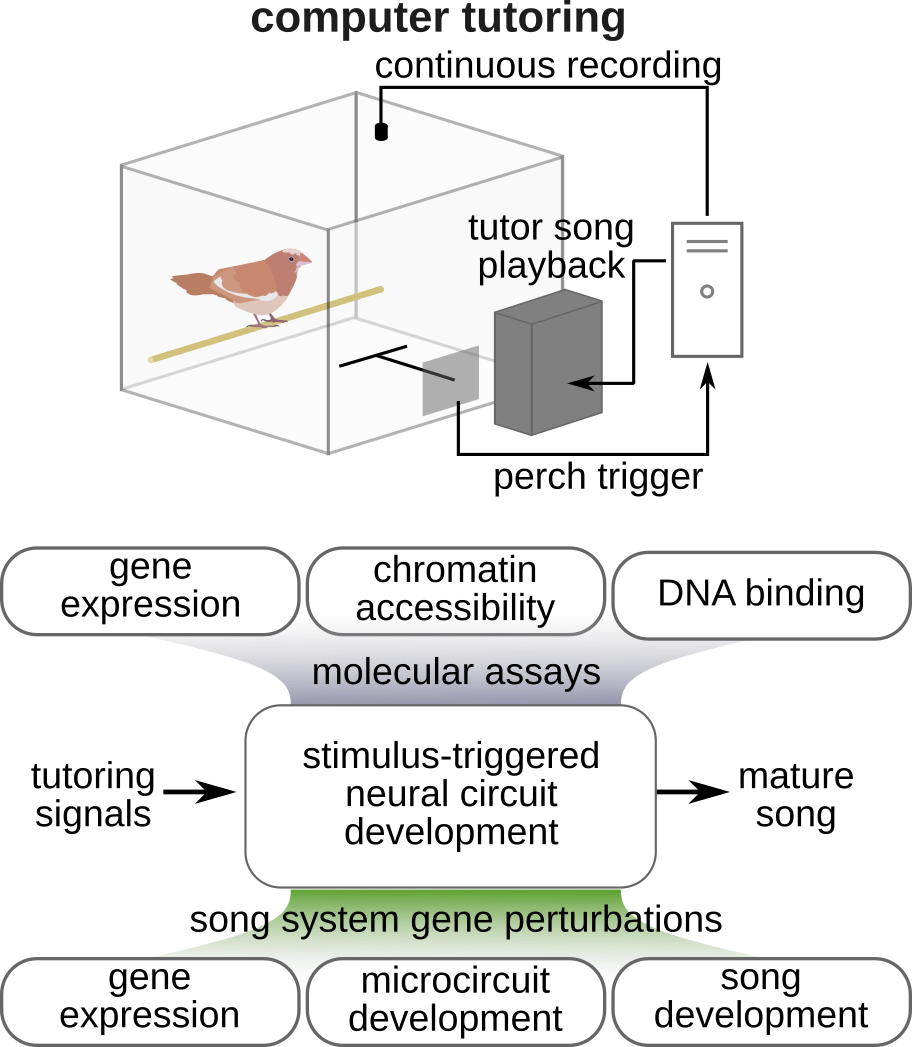

Evolution of motor control

Despite having strikingly different brain organizations, birds display a range of motor and cognitive abilities that rival or surpass the performance of many mammals. Remarkably, avian motor circuits are located in a distinct neural region from mammalian motor circuits, consistent with the independent evolution of pallial motor control in birds and mammals.

The lab studies the similarities and differences in the cellular composition, organization, and developmental histories of these motor systems, to understand how similar neural circuits can develop from distinct developmental starting points.